Miguel de Cervantes, the great Spanish writer, served as a Marine under the chivalric Don Juan of Austria, in the Holy League’s fleet during the

Battle of Lepanto. This great naval battle, which took place on October 7

th, 1571, defeated the plans of the Ottoman Empire to further the spread of Islam into Europe. Cervantes, although he was ill before battle, managed to fight with distinction, and suffered three gunshot wounds, one of which left his left arm useless — but as he later wrote, he “

had lost the movement of the left hand for the glory of the right,” since he was proud of his military service while gaining fame from his writing.

The Church, in commemoration of this great battle, instituted the feast of Our Lady of Victories, now called the Feast of the Most Holy Rosary of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Cervantes is most famous for his book

El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha (

The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha), better known as simply

Don Quixote. According the book’s

article on Wikipedia, “It follows the adventures of Alonso Quijano, an hidalgo who reads so many chivalric novels that he decides to set out to revive chivalry, under the name Don Quixote. He recruits a simple farmer, Sancho Panza, as his squire, who often employs a unique, earthly wit in dealing with Don Quixote’s rhetorical orations on antiquated knighthood.”

Cervantes’ novel, at the time of its publication, was widely celebrated as a comedy, and it became so familiar that the book became the model for the modern Spanish language, giving it a place similar to Luther’s translation of the Bible into German, or the influence of Dante’s Divine Comedy on Italian. He was a contemporary of William Shakespeare, and their works show a number of similarities.

Don Quixote is widely considered to be the first modern novel; it rejects the symbolism of Medieval fiction and its serious martial themes, and instead concentrates on psychology and everyday life in a humorous manner.

However, by the time of the French Revolution, the book became interpreted romantically, where the foolish main character of the book was depicted as an idealistic dreamer who is rejected by society. We see this romanticism in the song

The Impossible Dream (or

Don Quixote’s Quest) from the popular 1965 Broadway play

Man of La Mancha, here performed by Ed Ames on October 4

th, 2008:

Don Quixote is perhaps responsible for killing an entire genre of literature—and it was a Christian genre. In reading stories of noble knights and kings, we are reminded that the lowliest Christian peasant is a solider doing spiritual battle, and has the high dignity of being a member of the Body of Christ and the Royal Priesthood of the faithful, and that even the greatest of Kings also must serve a higher power. The modernist novel reduces everyone to the lowest common materialist denominator.

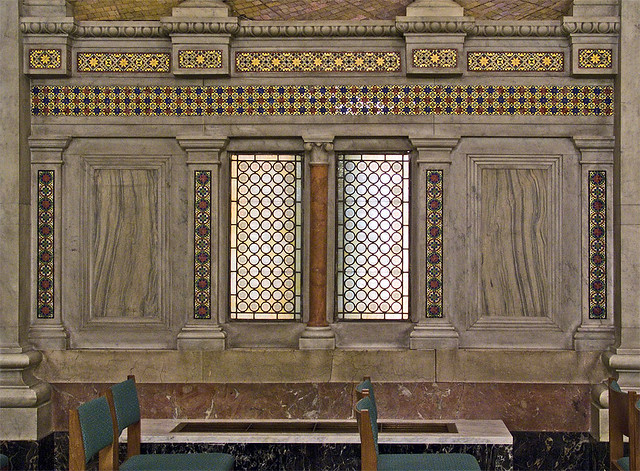

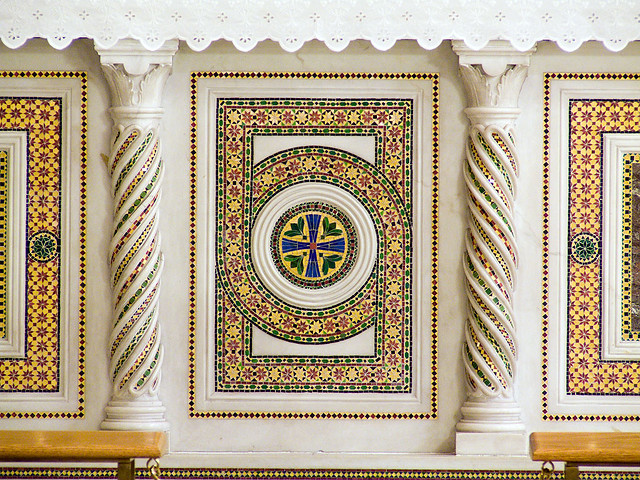

Don Quixote parodies many ancient Spanish poems, and as it is our goal to re-evaluate Modernism, let’s revisit some of these poems to discover their true value. These were translated into English by

John Gibson Lockhart, and published in his book

Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic. The illustrations here come from an

edition of the book made by several artists including Owen Jones, the famed Welsh art theorist I wrote about

here.

King Rodrigo was the last Visigothic ruler in Hispania, whose Christian realm was taken by the Moors.

The Lamentation of Don Roderick.

I. THE hosts of Don Rodrigo were scatter'd in dismay,

When lost was the eighth battle, nor heart nor hope had they ;

He, when he saw that field was lost, and all his hope was flown,

He turn'd him from his flying host, and took his way alone.

II. His horse was bleeding, blind, and lame he could no farther go ;

Dismounted, without path or aim, the King stepp'd to and fro ;

It was a sight of pity to look on Roderick,

For, sore athirst and hungry, he stagger'd faint and sick.

III. All stain'd and strew'd with dust and blood, like to some smouldering brand

Pluck'd from the flame Rodrigo shew'd : his sword was in his hand,

But it was hack'd into a saw of dark and purple tint ;

His jewell'd mail had many a flaw, his helmet many a dint.

IV. He climb'd unto a hill top, the highest he could see,

Thence all about of that wide route his last long look took he ;

He saw his royal banners, where they lay drench'd and torn,

He heard the cry of victory, the Arab's shout of scorn.

V. He look'd for the brave captains that had led the hosts of Spain,

But all were fled except the dead, and who could count the slain !

Where'er his eye could wander, all bloody was the plain,

And while thus he said, the tears he shed run down his cheeks like rain

VI. “Last night I was the King of Spain to-day no king am I ;

Last night fair castles held my train, to-night where shall I lie ?

Last night a hundred pages did serve me on the knee

To-night not one I call mine own : not one pertains to me.

VII. “O luckless, luckless was the hour, and cursed was the day,

When I was born to have the power of this great signiory !

Unhappy me, that I should see the sun go down to-night !

O Death, why now so slow art thou, why fearest thou to smite ?”

We often forget the Germanic history of Spain, but in this lament, perhaps we can see the melancholy often found in the ancient poems of the North, mourning for the loss of the good things in life, as found in the Anglo-Saxon poem

The Wanderer. But laments are also found in Sacred scripture, making up a large part of the book of Psalms. These are an embarrassment to modernist religionists who are always optimistic about human progress.

After the King's great military loss, he needed an extreme penance, for aren't the sins of the great worthy of far more reparation than the sins of the multitude? Unfortunately, the translator Lockhart, in his notes on this poem, is rather dismissive as he is with many of the poems. Rather, in this story, the defeated King shows true humility and sorrow for his wrongdoing.

The Penitence of Don Roderick.

I. IT was when the King Rodrigo had lost his realm of Spain,

In doleful plight he held his flight o'er Guadalete's plain ;

Afar from the fierce Moslem he fain would hide his wo,

And up among the wilderness of mountains he would go.

II. There lay a shepherd by the rill, with all his flock beside him ;

He ask'd him where upon his hill a weary man might hide him.

“Not far” quoth he, “within the wood dwells our old Eremite ;

He in his holy solitude will hide ye all the night.”

III. “Good friend,” quoth he, “I hunger.”—“Alas !” the shepherd said, -

“My scrip no more containeth but one little loaf of bread.”

The weary King was thankful, the poor man's loaf he took ;

He by him sate, and while he ate, his tears fell in the brook.

IV. From underneath his garment the King unlock'd his chain,

A golden chain with many a link, and the royal ring of Spain ;

He gave them to the wondering man, and with heavy steps and slow

He up the wild his way began, to the hermitage to go.

V. The sun had just descended into the western sea,

And the holy man was sitting in the breeze beneath his tree ;

“I come, I come, good father, to beg a boon from thee :

This night within thy hermitage give shelter unto me.”

VI. The old man look'd upon the King, he scann'd him o'er and o'er ;

He look'd with looks of wondering, he marvell'd more and more ;

With blood and dust distained was the garment that he wore,

And yet in utmost misery a kingly look he bore.

VII. “Who art thou, weary stranger ? This path why hast thou ta’en ?”

“I am Rodrigo ; yesterday men call'd me King of Spain ;

I come to make my penitence within this lonely place ;

Good father, take thou no offense, for God and Mary’s grace.”

VIII. The hermit look'd with fearful eye upon Rodrigo's face,

“Son, mercy dwells with the Most High not hopeless is thy case ;

Thus far thou well hast chosen, I to the Lord will pray,

He will reveal what penance may wash thy sin away.”

IX. Now, God us shield ! it was reveal'd that he his bed must make

Within a tomb, and share its gloom with a black and living snake.

Rodrigo bow'd his humbled head when God's command he heard,

And with the snake prepared his bed, according to the word.

X. The holy Hermit waited till the third day was gone,

Then knock'd he with his finger upon the cold tombstone ;

“Good king, good king,” the Hermit said, “now an answer give to me,

How fares it with thy darksome bed and dismal company ?”

XI. “Good father,” said Rodrigo, “the snake hath touch'd me not,

Pray for me, holy Hermit, I need thy prayers, God wot ;

Because the Lord his anger keeps, I lie unharmed here ;

The sting of earthly vengeance sleeps ; a worser pain I fear.”

XII. The Eremite his breast did smite when thus he heard him say,

He turn'd him to his cell, that night he loud and long did pray ;

At morning hour he came again, then doleful moans heard he,

From out the tomb the cry did come of gnawing misery.

XIII. He spake, and heard Rodrigo’s voice ; “O Father Eremite,

He eats me now, he eats me now, I feel the adder's bite ;

The part that was most sinning my bed-fellow doth rend,

There had my curse beginning, God grant it there may end !”

XIV. The holy man made answer in words of hopeful strain,

He bade him trust the body's pang would save the spirit's pain.

Thus died the good Rodrigo, thus died the King of Spain ;

Wash'd from offence his spirit hence to God its flight hath ta'en.

The Moorish King demanded an odious tribute from his Christian vassals, that of one hundred virgins per annum. The curious modern notions about women are hardly to be found in the medieval literature, and so the role of women found in that literature is far richer than one might suspect. Here we find a young maiden demanding that her King

act like a man, and

not pay the tribute:

The Maiden Tribute.

I. THE noble King Ramiro within the chamber sate,

One day, with all his barons, in council and debate,

When, without leave or guidance of usher or of groom,

There came a comely maiden into the council-room.

II. She was a comely maiden she was surpassing fair.

All loose upon her shoulders hung down her golden hair ;

From head to foot her garments were white as white may be ;

And while they gazed in silence, thus in the midst spake she.

III. “Sir King, I crave your pardon, if I have done amiss

In venturing before ye, at such an hour as this ;

But I will tell my story, and when my words ye hear,

I look for praise and honour, and no rebuke I fear.

IV. “I know not if I'm bounden to call thee by the name

Of Christian, King Ramiro ; for though thou dost not claim

A heathen realm's allegiance, a heathen sure thou art,

Beneath a Spaniard's mantle thou hidest a Moorish heart.

V. “For he who gives the Moor-King a hundred maids of Spain,

Each year when in its season the day comes round again ;

If he be not a heathen, he swells the heathen's train

'Twere better burn a kingdom than suffer such disdain.

VI. “If the Moslem must have tribute, make men your tribute-money,

Send idle drones to teaze them within their hives of honey ;

For when 'tis paid with maidens, from every maid there spring

Some five or six strong soldiers, to serve the Moorish King.

VII. “It is but little wisdom to keep our men at home,

They serve but to get damsels, who, when their day is come,

Must go, like all the others, the proud Moor's bed to sleep in

In all the rest they're useless, and nowise worth the keeping.

VIII. “And if 'tis fear of battle that makes ye bow so low,

And suffer such dishonour from God our Saviour's foe,

I pray you, sirs, take warning, ye'll have as good a fright,

If e'er the Spanish damsels arise themselves to right.

IX. “'Tis we have manly courage, within the breasts of women,

But ye are all hare-hearted, both gentlemen and yeomen.”

Thus spake that fearless maiden ; I wot when she was done,

Uprose the King Ramiro and his nobles every one.

X. The King call'd God to witness, that, come there weal or woe,

Thenceforth no maiden-tribute from out Castile should go ;

“At least I will do battle on God our Saviour's foe,

And die beneath my banner before I see it so.”

XI. A cry went through the mountains when the proud Moor drew near,

And trooping to Ramiro came every Christian spear ;

The blessed Saint lago, they called upon his name ;

That day began our freedom, and wiped away our shame.

The Christians, in avoiding the tribute, did battle with the Moors; according to legend, nearing the point of defeat, Saint James the Apostle—Santiago—appeared in full battle armor and routed the Moors. No more was the tribute paid, the tide had turned, and the long reconquest of Spain commenced.

It is such a strange stratagem

That our leaders now pursue;

They court the violent Moslem,

And hold Christ in deep distain.

Unlike good King Ramiro,

They scrape and bow with shame;

Will they undo with cunning,

What Iago did obtain?

It is difficult living under Dhimmitude. Christians must always make compromises:

The Wedding of the Lady Theresa.

I. 'TWAS when the fifth Alphonso in Leon held his sway,

King Abdalla of Toledo an embassy did send ;

He ask'd his sister for a wife, and in an evil day

Alphonso sent her, for he fear'd Abdalla to offend ;

He fear'd to move his anger, for many times before

He had received in danger much succour from that Moor.

II. Sad heart had fair Theresa when she their paction knew,

With streaming tears she heard them tell she 'mong the Moors must go,

That she, a Christian damosell, a Christian firm and true,

Must wed a Moorish husband, it well might cause her wo ;

But all her tears and all her prayers they are of small avail ;

At length she for her fate prepares, a victim sad and pale.

III. The King hath sent his sister to fair Toledo town,

Where then the Moor Abdalla his royal state did keep ;

When she drew near, the Moslem, from his golden throne, came down

And courteously received her, and bade her cease to weep ;

With loving words he press'd her, to come his bower within,

With kisses he caress'd her, but still she fear'd the sin.

IV. “Sir King, Sir King, I pray thee,” 'twas thus Theresa spake,

“I pray thee have compassion, and do to me no wrong ;

For sleep with thee I may not, unless the vows I break

Whereby I to the holy Church of Christ my Lord belong ;

But thou hast sworn to serve Mahoun, and if this thing should be,

The curse of God it must bring down upon thy realm and thee.

V. “The angel of Christ Jesu, to whom my heavenly Lord

Hath given my soul in keeping, is ever by my side ;

If thou dost me dishonour, he will unsheath his sword,

And smite thy body fiercely, at the crying of thy bride.

Invisible he standeth ; his sword, like fiery flame,

Will penetrate thy bosom, the hour that sees my shame.”

VI. The Moslem heard her with a smile ; the earnest words she said,

He took for bashful maiden's wile, and drew her to his bower.

In vain Theresa pray'd and strove she press'd Abdalla's bed,

Perforce received his kiss of love, and lost her maiden flower.

A woeful Woman there she lay, a loving lord beside,

And earnestly to God did pray her succour to provide.

VII. The Angel of Christ Jesu her sore complaint did hear,

And pluck'd his heavenly weapon from out its sheath unseen,

He waved the brand in his right hand, and to the King came near,

And drew the point o'er limb and joint, beside the weeping Queen.

A mortal weakness from the stroke upon the King did fall,

He could not stand when daylight broke, but on his knees must crawl.

VIII. Abdalla shudder'd inly, when he this sickness felt,

And call'd upon his Barons, his pillow to come nigh ;

“Rise up,” he said, “my liegemen,” as round his bed they knelt,

“And take this Christian lady, else certainly I die;

Let gold be in your girdles, and precious stones beside,

And swiftly ride to Leon, and render up my bride.”

IX. When they were come to Leon, Theresa would not go

Into her brother's dwelling, where her maiden years were spent ;

But o'er her downcast visage a white veil she did throw,

And to the ancient nunnery of Saint Pelagius went.

There long, from worldly eyes retired, a holy life she led ;

There she, an aged saint, expired—there sleeps she with the dead.

El Cid—Rodrigo Díaz de Bivar—is a great national hero of Spain. He served several rulers, and gained the admiration of all, being called

El Cid—the Lord—by the Moors and

El Campeador—the battle master—by the Christians.

The Cid and the Five Moorish Kings.

I. WITH fire and desolation the Moors are in Castille,

Five Moorish kings together, and all their vassals leal ;

They've pass'd in front of Burgos, through the Oca-Hills they've run,

They've plunder'd Belforado, San Domingo's harm is done

II. In Najara and Lograno there's waste and disarray :

And now with Christian captives, a very heavy prey,

With many men and women, and boys and girls beside,

In joy and exultation to their own realms they ride.

III. For neither king nor noble would dare their path to cross,

Until the good Rodrigo heard of this skaith and loss ;

In old Bivar the castle he heard the tidings told,

(He was as yet a stripling, not twenty summers old.)

IV. He mounted Bavieca, his friends he with him took,

He raised the country round him, no more such scorn to brook ;

He rode to the hills of Oca, where then the Moormen lay,

He conquer'd all the Moormen, and took from them their prey.

V. To every man had mounted he gave his part of gain,

Dispersing the much treasure the Saracens had ta'en ;

The Kings were all the booty himself had from the war,

Them led he to the castle, his strong-hold of Bivar.

VI. He brought them to his mother, proud dame that day was she :

They own'd him for their Signior, and then he set them free ;

Home went they, much commending Rodrigo of Bivar,

And sent him lordly tribute, from their Moorish realms afar.

Boldness and femininity, in the modern mind, are often strictly opposed, and one must not coexist with the other; but the Medieval heroine often combines boldness and femininity in a generally pleasing fashion, well suited to be a mate to the chivalrous gentleman. Here we find Ximena Gomez—who is featured in an earlier poem not copied here—who boldly asks for the hand of

El Cid in marriage.

The Cid's Courtship.

I. Now, of Rodrigo de Bivar great was the fame that run,

How he five Kings had vanquish'd, proud Moormen every one ;

And how, when they consented to hold of him their ground,

He freed them from the prison wherein they had been bound.

II. To the good King Fernando, in Burgos where he lay,

Came then Ximena Gomez, and thus to him did say

“I am Don Gomez' daughter, in Gormaz Count was he ;

Him slew Rodrigo of Bivar in battle valiantly.

III. “Now am I come before you, this day a boon to crave

And it is that I to husband may this Rodrigo have ;

Grant this, and I shall hold me a happy damosell,

Much honour'd shall I hold me, I shall be married well.

IV. “I know he's born for thriving, none like him in the land ;

I know that none in battle against his spear may stand ;

Forgiveness is well pleasing in God our Saviour's view,

And I forgive him freely, for that my sire he slew.”

V. Right pleasing to Fernando was the thing she did propose ;

He writes his letter swiftly, and forth his foot-page goes ;

I wot, when young Rodrigo saw how the King did write,

He leapt on Bavieca—I wot his leap was light.

VI. With his own troop of true men forthwith he took the way,

Three hundred friends and kinsmen, all gently born were they ;

All in one colour mantled, in armour gleaming gay,

New were both scarf and scabbard, when they went forth that day.

VII. The King came out to meet him, with words of hearty cheer ;

Quoth he, “My good Rodrigo, you are right welcome here ;

This girl Ximena Gomez would have ye for her lord,

Already for the slaughter her grace she doth accord.

VIII. “I pray you be consenting, my gladness will be great ;

You shall have lands in plenty, to strengthen your estate.”

“Lord King,” Rodrigo answers, “in this and all beside,

Command, and I'll obey you. The girl shall be my bride.”

IX. But when the fair Ximena came forth to plight her hand,

Rodrigo, gazing on her, his face could not command :

He stood and blush'd before her ; thus at the last said he

“I slew thy sire, Ximena, but not in villainy :

X. “In no disguise I slew him, man against man I stood ;

There was some wrong between us, and I did shed his blood.

I slew a man, I owe a man ; fair lady, by God's grace,

An honour’d husband thou shalt have in thy dead father’s place.”

This poem shows the Christian character of El Cid:

The Cid and the Leper.

I. HE has ta'en some twenty gentlemen, along with him to go,

For he will pay that ancient vow he to Saint James doth owe ;

To Compostello, where the shrine doth by the altar stand,

The good Rodrigo de Bivar is riding through the land.

II. Where'er he goes, much alms he throws, to feeble folk and poor ;

Beside the way for him they pray, him blessings to procure ;

For, God and Mary Mother, their heavenly grace to win,

His hand was ever bountiful : great was his joy therein.

III. And there, in middle of the path, a leper did appear ;

In a deep slough the leper lay, none would to help come near.

With a loud voice he thence did cry, “For God our Saviour's sake,

From out this fearful jeopardy a Christian brother take.”

IV. When Roderick heard that piteous word, he from his horse came down ;

For all they said, no stay he made, that noble champion ;

He reach'd his hand to pluck him forth, of fear was no account,

Then mounted on his steed of worth, and made the leper mount.

V. Behind him rode the leprous man ; when to their hostelrie

They came, he made him eat with him at table cheerfully ;

While all the rest from that poor guest with loathing shrunk away,

To his own bed the wretch he led, beside him there he lay.

VI. All at the mid-hour of the night, while good Rodrigo slept,

A breath came from the leprous man, it through his shoulders crept ;

Right through the body, at the breast, pass'd forth that breathing cold;

I wot he leap'd up with a start, in terrors manifold.

VII. He groped for him in the bed, but him he could not find,

Through the dark chamber groped he, with very anxious mind ;

Loudly he lifted up his voice, with speed a lamp was brought,

Yet nowhere was the leper seen, though far and near they sought.

VIII. He turn'd him to his chamber, God wot, perplexed sore

With that which had befallen—when lo ! his face before,

There stood a man, all clothed in vesture shining white :

Thus said the vision, “Sleepest thou, or wakest thou, Sir Knight ?”

IX. “I sleep not,” quoth Rodrigo ; “but tell me who art thou,

For, in the midst of darkness, much light is on thy brow ?”

“I am the holy Lazarus, I come to speak with thee ;

I am the same poor leper thou savedst for charity.

X. “Not vain the trial, nor in vain thy victory hath been ;

God favours thee, for that my pain thou didst relieve yestreen.

There shall be honour with thee, in battle and in peace,

Success in all thy doings, and plentiful increase.

XI. “Strong enemies shall not prevail, thy greatness to undo ;

Thy name shall make men’s cheeks full pale—Christians and Moslems too ;

A death of honour shalt thou die, such grace to thee is given,

Thy soul shall part victoriously, and be received in heaven.”

XII. When he these gracious words had said, the spirit vanish'd quite.

Rodrigo rose and knelt him down—he knelt till morning light ;

Unto the Heavenly Father, and Mary Mother dear,

He made his prayer right humbly, till dawn'd the morning clear.

A poem where

El Cid and the Holy Father the Pope both make a mistake—but all is forgiven:

The Excommunication of The Cid.

I. IT was when from Spain across the main the Cid had come to Rome,

He chanced to see chairs four and three beneath Saint Peter's dome.

“Now tell, I pray, what chairs be they ?” “Seven kings do sit thereon,

As well doth suit, all at the foot of the holy Father's throne.

II. “The Pope he sitteth above them all, that they may kiss his toe,

Below the keys the Flower-de-lys doth make a gallant show ;

For his great puissance, the King of France next to the Pope may sit,

The rest more low, all in a row, as doth their station fit.”

III. “Ha !” quoth the Cid, “now God forbid ! it is a shame, I wiss,

To see the Castle planted beneath the Flower-de-lys

No harm, I hope, good Father Pope although I move thy chair.”

In pieces small he kick'd it all, ('twas of the ivory fair.)

IV. The Pope's own seat he from his feet did kick it far away,

And the Spanish chair he planted upon its place that day ;

Above them all he planted it, and laugh'd right bitterly ;

Looks sour and bad I trow he had, as grim as grim might be.

V. Now when the Pope was aware of this, he was an angry man,

His lips that night, with solemn rite, pronounced the awful ban ;

The curse of God, who died on rood, was on that sinner's head

To hell and woe man's soul must go if once that curse be said,

VI. I wot, when the Cid was aware of this, a woeful man was he,

At dawn of day he came to pray at the blessed Father's knee :

“Absolve me, blessed Father, have pity upon me,

Absolve my soul, and penance I for my sin will dree.”

VII. “Who is this sinner,” quoth the Pope, “that at my foot doth kneel ?”

—“I am Rodrigo Diaz—a poor Baron of Castille.”—

Much marvell'd all were in the hall, when that name they heard him say,

—“Rise up, rise up,” the Pope he said, “I do thy guilt away ;—

VIII. “I do thy guilt away,” he said — “and my curse I blot it out—

God save Rodrigo Diaz, my Christian champion stout ; —

I trow, if I had known thee, my grief it had been sore,

To curse Ruy Diaz de Bivar, God’s scourge upon the Moor.”—

Our selection of historical poems starts with the conquest of Spain by the Moors, while this last one describes the Christian reconquest of Spain. Please note that while these poems point out religious differences, the Moors are

always depicted as being noble. It is not good that Christians are ruled by Moslems, and indeed the Holy Catholic faith is superior, but this is

not seen as impugning on the character of the Moors, for are they not too made in the Image and Likeness of God? Demonization and hatred of enemies, and racism and bigotry are the products of

modernism.

The Flight From Granada.

I. THERE was crying in Granada when the sun was going down,

Some calling on the Trinity, some calling on Mahoun ;

Here pass'd away the Koran, there in the Cross was borne,

And here was heard the Christian bell, and there the Moorish horn ;

II. Te Deum Laudamus was up the Alcala sung :

Down from the Alhamra's minarets were all the crescents flung ;

The arms thereon of Arragon they with Castille's display ;

One king comes in triumph, one weeping goes away.

III. Thus cried the weeper, while his hands his old white beard did tear,

“Farewell, farewell, Granada ! thou city without peer ;

Woe, woe, thou pride of Heathendom, seven hundred years and more

Have gone since first the faithful thy royal sceptre bore.

IV. “Thou wert the happy mother of an high renowned race ;

Within thee dwelt a haughty line that now go from their place ;

Within thee fearless knights did dwell, who fought with mickle glee-

The enemies of proud Castille, the bane of Christientie.

V. “The mother of fair dames wert thou, of truth and beauty rare,

Into whose arm's did courteous knights for solace sweet repair ;

For whose dear sakes the gallants of Afric made display

Of might in joust and battle on many a bloody day :

VI. “Here gallants held it little thing for ladies' sake to die,

Or for the Prophet's honour, and pride of Soldanry ;

For here did valour flourish, and deeds of warlike might

Ennobled lordly palaces, in which was our delight.

VII. “The gardens of thy Vega, its fields and blooming bowers

Woe, woe ! I see their beauty gone, and scatter'd all their flowers.

No reverence can he claim the King that such a land hath lost,

On charger never can he ride, nor be heard among the host

But in some dark and dismal place, where none his face may see,

There, weeping and lamenting, alone that King should be.”

VIII. Thus spake Granada's King as he was riding to the sea,

About to cross Gibraltar's Strait away to Barbary :

Thus he in heaviness of soul unto his Queen did cry.

(He had stopp'd and ta'en her in his arms, for together they did fly.)

IX. “Unhappy King ! whose craven soul can brook" (she 'gan reply,)

“To leave behind Granada, who hast not heart to die

Now for the love I bore thy youth thee gladly could I slay,

For what is life to leave when such a crown is cast away ?”

The book includes a number of Moorish poems, including this one about bull fighting:

The Bull-Fight Of Ganzul.

I. KING ALMANZOR of Grenada, he hath bid the trumpet sound,

He had summon'd all the Moorish Lords, from the hills and plains around ;

From Vega and Sierra, from Betis and Xenil,

They have come with helm and cuirass of gold and twisted steel.

II. Tis the holy Baptist's feast they hold in royalty and state,

And they have closed the spacious lists, beside the Alhamra's gate ;

In gowns of black with silver laced within the tented ring,

Eight Moors to fight the bull are placed in presence of the King.

III. Eight Moorish lords of valour tried, with stalwart arm and true,

The onset of the beasts abide come trooping furious through ;

The deeds they've done, the spoils they've won, fill all with hope and trust,

Yet ere high in heaven appears the sun, they all have bit the dust.

IV. Then sounds the trumpet clearly, then clangs the loud tambour,

Make room, make room for Ganzul—throw wide, throw wide the door ;

Blow, blow the trumpet clearer still, more loudly strike the drum,

The Alcaydé of Agalva to fight the bull doth come.

V. And first before the King he pass'd, with reverence stooping low,

And next he bow'd him to the Queen, and the Infantas all a-rowe ;

Then to his lady's grace he turn'd, and she to him did throw

A scarf from out her balcony was whiter than the snow.

VI. With the life-blood of the slaughter'd lords all slippery is the sand,

Yet proudly in the centre hath Ganzul ta'en his stand ;

And ladies look with heaving breast, and lords with anxious eye,

But the lance is firmly in its rest, and his look is calm and high.

VII. Three bulls against the knight are loosed, and two come roaring on,

He rises high in stirrup, forth stretching his rejon ;

Each furious beast upon the breast he deals him such a blow,

He blindly totters and gives back across the sand to go.

VIII. “Turn, Ganzul, turn,” the people cry—the third comes up behind,

Low to the sand his head holds he, his nostrils snuff the wind ;

The mountaineers that lead the steers, without stand whispering low,

“Now thinks this proud Alcaydé to stun Harpado so ?”

IX. From Guadiana comes he not, he comes not from Xenil,

From Guadalarif of the plain, or Barves of the hill ;

But where from out the forest burst Xarama's waters clear,

Beneath the oak trees was he nursed, this proud and stately steer.

X. Dark is his hide on either side, but the blood within doth boil,

And the dun hide glows, as if on fire, as he paws to the turmoil.

His eyes are jet, and they are set in crystal rings of snow ;

But now they stare with one red glare of brass upon the foe.

XI. Upon the forehead of the bull the horns stand close and near,

From out the broad and wrinkled skull, like daggers they appear ;

His neck is massy, like the trunk of some old knotted tree,

Whereon the monster's shagged mane, like billows curl'd, ye see.

XII. His legs are short, his hams are thick, his hoofs are black as night,

Like a strong flail he holds his tail in fierceness of his might ;

Like something molten out of iron, or hewn from forth the rock,

Harpado of Xarama stands, to bide the Alcaydé's shock.

XIII. Now stops the drum—close, close they come—thrice meet, and thrice give back ;

The white foam of Harpado lies on the charger's breast of black

The white foam of the charger on Harpado’s front of dun—

Once more advance upon his lance—once more, thou fearless one !

XIV. Once more, once more ;—in dust and gore to ruin must thou reel—

In vain, in vain thou tearest the sand with furious heel—

In vain, in vain, thou noble beast, I see, I see thee stagger,

Now keen and cold thy neck must hold the stern Alcaydé's dagger !

XV. They have slipp'd a noose around his feet, six horses are brought in,

And away they drag Harpado with a loud and joyful din.—

Now stoop thee, lady, from thy stand, and the ring of price bestow

Upon Ganzul of Agalva, that hath laid Harpado low.

Following are two romantic ballads:

Melisendra.

I. AT Sansueña, in the tower, fair Melisendra lies,

Her heart is far away in France, and tears are in her eyes ;

The twilight shade is thickening laid on Sansueña's plain,

Yet wistfully the lady her weary eyes doth strain.

II. She gazes from the dungeon strong, forth on the road to Paris,

Weeping, and wondering why so long her Lord Gayferos tarries,

When lo ! a knight appears in view a knight of Christian mien,

Upon a milk-white charger he rides the elms between.

III. She from her window reaches forth her hand a sign to make,

“O if you be a knight of worth, draw near for mercy's sake ;

For mercy and sweet charity, draw near, Sir Knight to me,

And tell me if ye ride to France, or whither bowne ye be.

IV. “O, if ye be a Christian knight, and if to France you go,

I pr'ythee tell Guyferos that you have seen my woe ;

That you have seen me weeping, here in the Moorish tower,

While he is gay by night and day, in hall and lady's bower.

V. “Seven summers have I waited, seven winters long are spent,

Yet word of comfort none he speaks, nor token hath he sent ;

And if he is weary of my love, and would have me wed a stranger,

Still say his love is true to him nor time nor wrong can change her.”

VI. The knight on stirrup rising, bids her wipe her tears away,

“My love, no time for weeping, no peril save delay

Come, boldly spring, and lightly leap no listening Moor is near us,

And by dawn of day we’ll be far away” so spake the Knight Guyferos.

VII. She hath made the sign of the Cross divine, and an Ave she hath said,

And she dares the leap both wide and deep that damsel without dread ;

And he hath kiss'd her pale pale cheek, and lifted her behind,

Saint Denis speed the milk-white steed no Moor their path shall find.

Lady Alda's Dream.

I. IN Paris sits the lady that shall be Sir Roland's bride,

Three hundred damsels with her, her bidding to abide ;

All clothed in the same fashion, both the mantle and the shoon

All eating at one table, within her hall at noon :

All, save the Lady Alda, she is lady of them all,

She keeps her place upon the dais, and they serve her in her hall ;

The thread of gold a hundred spin, the lawn a hundred weave,

And a hundred play sweet melody within Alda's bower at eve.

II. With the sound of their sweet playing, the lady falls asleep,

And she dreams a doleful dream, and her damsels hear her weep ;

There is sorrow in her slumber, and she waketh with a cry,

And she calleth for her damsels, and swiftly they come nigh.

“ Now, what is it, Lady Alda,” (you may hear the words they say,)

“Bringeth sorrow to thy pillow, and chaseth sleep away ?”

“O, my maidens !” quoth the lady, “my heart it is full sore !

I have dreamt a dream of evil, and can slumber never more.

III. “For I was upon a mountain, in a bare and desert place,

And I saw a mighty eagle, and a faulcon he did chase ;

And to me the faulcon came, and I hid it in my breast,

But the mighty bird, pursuing, came and rent away my vest ;

And he scatter'd all the feathers, and blood was on his beak,

And ever, as he tore and tore, I heard the faulcon shriek :

Now read my vision, damsels, now read my dream to me,

For my heart may well be heavy that doleful sight to see.”

IV. Out spake the foremost damsel was in her chamber there

(You may hear the words she says,) “Oh ! my lady's dream is fair

The mountain is St Denis' choir ; and thou the faulcon art,

And the eagle strong that teareth the garment from thy heart,

And scattereth the feathers, he is the Paladin

That, when again he comes from Spain, must sleep thy bower within ;

Then be blythe of cheer, my lady, for the dream thou must not grieve,

It means but that thy bridegroom shall come to thee at eve.”

V. “If thou hast read my vision, and read it cunningly”

Thus said the Lady Alda, “thou shalt not lack thy fee.”

But wo is me for Alda ! there was heard, at morning hour,

A voice of lamentation within that lady's bower ;

For there had come to Paris a messenger by night,

And his horse it was a-weary, and his visage it was white ;

And there's weeping in the chamber, and there's silence in the hall,

For Sir Roland has been slaughter'd, in the chase of Roncesval.

Christians and Moors alike celebrated the feast-day of Saint John the Baptist. Although our translator rejects the following as barbarous superstition, shouldn't we sanctify the year by celebrating the great Saints? Shouldn't we ask for God's blessings and the intercession of the Saints?

Song for the morning of the Day of St. John the Baptist.

COME forth, come forth, my maidens, 'tis the day of good St John,

It is the Baptist's morning that breaks the hills upon,

And let us all go forth together, while the blessed day is new,

To dress with flowers the snow-white wether, ere the sun has dried the dew.

Come forth, come forth, my maidens, the woodlands all are green,

And the little birds are singing the opening leaves between,

And let us all go forth together, to gather trefoil by the stream,

Ere the face of Guadalquiver glows beneath the strengthening beam.

Come forth, come forth, my maidens, and slumber not away

The blessed blessed morning of the holy Baptist's day ;

There's trefoil on the meadow, and lilies on the lee,

And hawthorn blossoms on the bush, which you must pluck with me.

Come forth, come forth, my maidens, the air is calm and cool,

And the violet blue far down ye'll view, reflected in the pool ;

The violets and the roses, and the jasmines all together,

We'll bind in garlands on the brow of the strong and lovely wether.

Come forth, come forth, my maidens, we'll gather myrtle boughs,

And we all shall learn from the dews of the fern, if our lads will keep their vows.

If the wether be still, as we dance on the hill, and the dew hangs sweet on the flowers,

Then we'll kiss off the dew, for our lovers are true, and the Baptist's blessing is ours.

It is the Baptist's morning that breaks the hills upon ;

And let us all go forth together, while the blessed day is new,

To dress with flowers the snow-white wether, ere the sun has dried the dew.

Here are two ballads of loves who were lost:

Juliana.

I. “OFF ! off! ye hounds ! in madness an ill death be your doom !

The boar ye kill'd on Thursday on Friday ye consume !

Aye me ! and it is now seven years I in this valley go ;

Barefoot I wander, and the blood from out my nails doth flow.

II. “I eat the raw flesh of the boar, I drink his red blood here,

Seeking, with heavy heart and sore, my Princess and my dear.

'Twas on the Baptist's morning the Moors my Princess found,

While she was gathering roses upon her father’s ground.”

III. Fair Juliana heard his voice where by the Moor she lay,

Even in the Moor's encircling arms she heard what he did say ;

The lady listen'd, and she wept within that guarded place,

While her Moor Lord beside her slept the tears fell on his face.

Valladolid.

I. MY heart was happy when I turn'd from Burgos to Valladolid ;

My heart that day was light and gay, it bounded like a kid.

I met a Palmer on the way, my horse he bade me rein

“I left Valladolid to-day, I bring thee news of pain !

The lady-love whom thou dost seek in gladness and in cheer,

Closed is her eye, and cold her cheek, I saw her on her bier.

II. “The Priests went singing of the Mass, my voice their song did aid ;

A hundred knights with them did pass to the burial of the Maid ;

And damsels fair went weeping there, and many a one did say,

Poor Cavalier ! he is not here ’tis well he’s far away.”

I fell when thus I heard him speak, upon the dust I lay,

I thought my heart would surely break, I wept for half a day.

III. When evening came I rose again, the Palmer held my steed.

And swiftly rode I o'er the plain to dark Valladolid.

I came unto the sepulchre where they my love had laid,

I bow'd me down beside the bier, and there my moan I made :

“O take me, take me to thy bed, I fain would sleep with thee !

My love is dead, my hope is fled, there is no joy for me !”

IV. I heard a sweet voice from the tomb, I heard her voice so clear,

“Rise up, rise up, my knightly love, thy weeping well I hear ;

Rise up and leave this darksome place, it is no place for thee,

God yet will send thee helpful grace, in love and chivalry ;

Though in the grave my bed I have, for thee my heart is sore,

’Twill ease my heart if thou depart thy peace may God restore !”

Modernist fiction gives us more

facts, but at the expense of the heart and wisdom, while its emphasis on psychology is invariably a justification for lack of

virtue. The old ballads still have value, on several levels of meaning.